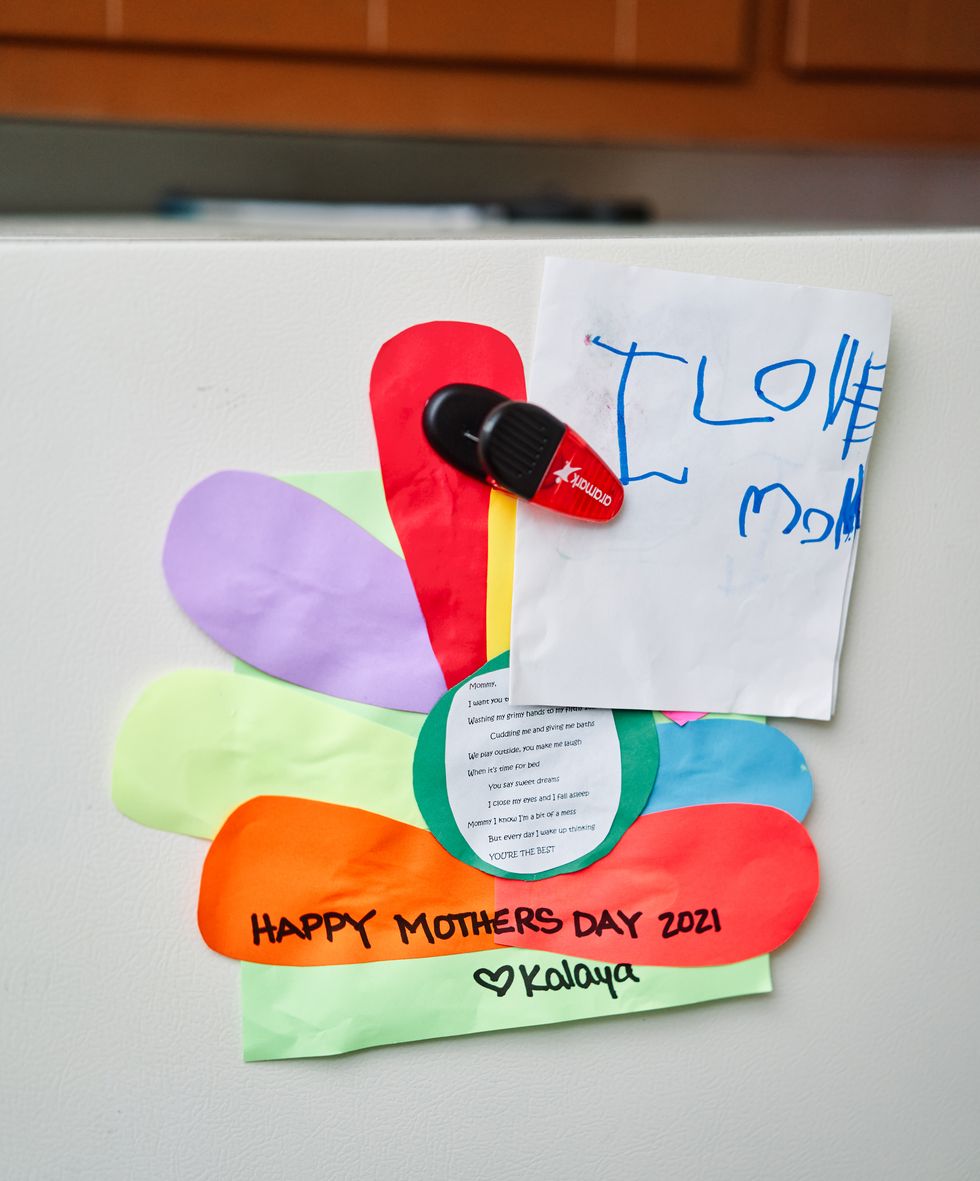

“I'm just hoping to create those good memories, so she won't remember all this, so it won't be at the forefront for her,” Latrish Oseko told me. She was planning a fifth-birthday party for her daughter, Ka’laya, and some of her friends. They were going to Sky Zone, a trampoline-park franchise, near their home in Wilmington, Delaware. It was a birthday celebration, but also a moment to rejoice that they’d made it through a terrible year—and that they had a home again.

Oseko knew she was in trouble as soon as the pandemic hit. “I was a contract worker, so I thought I would probably be one of the first people to be laid off,” she said of her job as an administrative assistant. Sure enough, her employer cut her hours in half at the beginning of April 2020. A month later, they dropped her entirely. Her boyfriend, Keith, was able to hold onto his job at a local university, though he was furloughed for a period. “But I was glad he was able to stay employed,” Latrish added, “because little did we know that my landlord was going to sell our house. That's how we became homeless—he sold the house during the pandemic.”

Their lease was up in July, but Oseko’s landlord informed them in May—just after she lost her job—that he wouldn’t be renewing them because he was selling the property. Oseko says she didn’t want to stay and fight and risk an eviction that could follow her for years. While Keith had held onto some of his income, it wasn’t enough to match the requirement at the properties they looked at that renters make three times the monthly rent. Oseko says she was told her unemployment benefits didn’t count as income (despite this practice being illegal), even if they were based on income she’d lost through no fault of her own .

When the July day arrived where they had to be out of their home, all the notice their landlord had given them hadn’t made much difference. They had the money to put a roof over their heads, but not enough of the right kind of money. They’d fallen through the cracks into a desperate situation, made worse when there were no shelters available in their area. They ended up at a Motel 6, which cost them $2,600 a month.

“People with mortgages don't pay that [much],” Oseko said, “unless you're rich.”

It’s expensive to be poor. When you’ve got money, you can build wealth. When you don’t, everything around you seems to be sucking away what you have. “Even the food bill was outrageous, because we ate out every night,” Oseko said. “We had to, we had no place to cook. We would go to Acme and get two orders of fried chicken, and try to make it last a few nights. When Keith was working, he’d take his lunch out of that. But more times than not, we’d have to eat from a restaurant every night. We still had to pay for gas, the car payments. You just think, ‘Oh my God, it's gotten so much more expensive to be homeless.’”

They weren’t alone. The surroundings offered constant reminders that they and others around them were living on the edge. “In the motel, I cried almost every day for one reason or another,” Oseko told me. "You will see somebody couldn't pay their rent. And they'll have two and three children with clothes baskets, with bags of clothes, waiting for a ride because they can't afford a night at the motel.”

Oseko couldn’t bear the thought of taking her daughter out of daycare. It was expensive, and there had been a few COVID outbreaks there, but it was her daughter’s connection to her friends—and one last shred of normalcy. Osenko worried Ka’laya had begun to pick up on her anxiety and her desperation. Oseko would sit and watch the 6 o’clock news, then the 10 o’clock, then the 11, to see if Congress had passed an update to the extended unemployment benefits–or anything else that might offer them a way out of paying so much for something that never felt like home. She found herself increasingly angry with our elected representatives, and she made no distinction between Democrats and Republicans, as they dragged their feet on extending boosted unemployment benefits and other COVID relief last year.

“It’s not the government’s fault” what happened to her, she says, “but they can at least hold up their end of the bargain. Don't make us wait. Why make us wait? See we're suffering. That is so painful, to know that a person has control at their fingertips, and then they just take their time and have their back and forth. They don't have to worry about where the next meal is coming from. They don't have to worry about their child, whether they’re safe in daycare. They don't have to worry about will they have a bed to sleep on tonight.”

Get unlimited access to all Esquire's news and politics coverage.

Which makes her work with Unemployed Action, a project of the Center for Popular Democracy working to organize unemployed workers, both personal and pressing. “It gives me a personal feeling like I'm doing something, I'm helping, I'm not just wallowing in what I've been through,” she says. The movement has set its sights on durable reform to the unemployment system. They want permanent triggers for boosted benefits inserted in the law so that when the economic situation deteriorates to a certain point, Congress does not have to get itself together and pass a law to avoid American families like Oseko’s from plunging into desperation. “The time that Congress has to pass these bills, it shouldn't be that we have to write our senators, and our teeth are chattering, and we're scared to have holiday dinners and buy things for our families like we normally would, because they want to argue back and forth. We shouldn't have to keep going to Congress for these things.” (They’ve seen some progress on that front as part of the Biden administration’s proposed American Families Plan.)

Oseko has also run workshops through Unemployed Action, including some focused on the specific challenges people of color face navigating the system. She has recruited people to the organization who were struggling to sign up or secure benefits. “Just because I'm getting unemployment doesn't mean that I'm not going to pay,” she explained. “I'm going to pay because I want a roof over my head. I'm sure there were a few bad apples that just said, ‘Okay, it's a pandemic, I don't have to pay.’ But most of us want a roof over our head, and will do whatever it takes to keep it and to get one.”

Oseko also favors some sort of national unemployment program to replace the various state setups, in part because of all the hurdles she’s run up against in Delaware. Signing up was easy for her—not true for everyone, as some horror stories on Reddit’s r/unemployment demonstrate—but she’s had issues since. “I have been waiting for my 1099 forms, so I can file my taxes, since January,” she said, describing all the problems tied to having changed her address in the last year—a not-uncommon development for people who are unemployed. “I have been chasing this 1099 form down for forever, and the lady just emailed it to me today like nothing. And a lot of states on their—Ka’laya, please get up here,” she paused to corral her daughter. They were at the park. “A lot of states, right on their unemployment website, will allow you to go print the form. Why can't Delaware do that with this technology that we have today?”

One way the state of Delaware did help her, though, was by connecting her to a program called Family Promise, a nonprofit aiming to stabilize the lives of families with children experiencing homelessness. A Delaware affiliate branch of the organization assigned her a caseworker and, in September, helped them find an apartment that would take them. But even then, it wasn’t over. The day that they signed their new lease and were finally set to move out of the motel, she got a call from Ka’laya’s daycare: due to a Covid outbreak, they’d have to shut down for two weeks, and Latrish would have to pick her up by two o’clock. “We're trying to move stuff in my little Kia Soul, from the motel to our apartment now. And we're making trips, and I had to just stop it, and we had to pay for an extra night.”

It was one last bump in a grinding, exhausting journey. “I really don't want to be on unemployment,” Oseko said. “Me and my mom held two and three jobs when we were growing up. Anything from housekeeping to picking crabs—we're from the eastern shore of Maryland.” She has been interviewing. “I just want to show Ka’laya that this is what you do, even when a pandemic has you down. You've been through the worst by five. This is what you do every day. You keep pounding the pavement. She’ll say, ‘Mom, why are you on your phone?’ I say, ‘Ka’laya, I'm applying for jobs through Indeed.’” But so many interviews that seemed to go well—full of smiles and warmth and understanding—end badly. “You get ghosted, and you don't even get a letter that they chose somebody else.” For now, she and her family are back in a home—not a motel that feels like they’re on their way somewhere else. Well, other than Sky Zone.

Jack Holmes is a senior staff writer at Esquire, where he covers politics and sports. He also hosts Unapocalypse, a show about solutions to the climate crisis.